Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow Press Kit

Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow explores the struggle for full citizenship and racial equality that unfolded in the 50 years after the Civil War. When slavery ended in 1865, a period of Reconstruction began, leading to such achievements as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. By 1868, all persons born in the United States were citizens and equal before the law. But efforts to create an interracial democracy were contested from the start. A harsh backlash ensued, ushering in a half century of the “separate but equal” age of Jim Crow. Opening to mark the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the exhibition is organized chronologically from the end of the Civil War to the end of World War I and highlights the central role played by African Americans in advocating for their rights.

This exhibition has been organized by the New-York Historical Society.

ST. PAUL, Minn (Jan. 17, 2024) – Black Citizenship in the Age of Jim Crow explores African Americans' fight for racial equality and full citizenship that unfolded in the 50 years following the Civil War. Through art, artifacts, and photographs, visitors to the Minnesota History Center will experience the legacy of Black advancement, resilience, and resistance in the face of opposition from many white Americans during these transformative decades, which are still relevant today.

The exhibition's debut on February 3 coincides with the first week of Black History Month. This exhibition, organized by the New-York Historical Society, will provide History Center visitors a space to honor, acknowledge, and celebrate the contributions of Black Americans. It also allows an opportunity to pause and reflect on the Black experience in the United States. The exhibition will run through June 9, 2024.

Opened by the New-York Historical Society in 2018 to mark the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, this traveling exhibition follows the journey of African Americans from the end of the Civil War to the end of World War I. Exhibition highlights include:

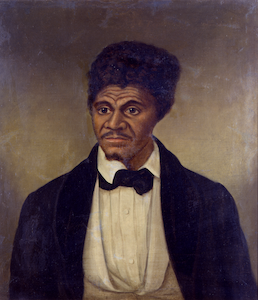

- portrait of Dred Scott (ca. 1857), an enslaved person from Missouri, transferred to Historic Fort Snelling in 1836, who sued for his freedom and lost after the US Supreme Court ruled that no Black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a US citizen;

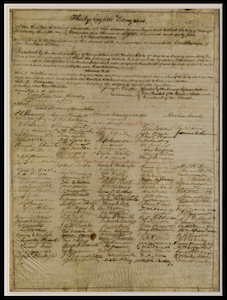

- Thirteenth Amendment (1865), signed by President Abraham Lincoln, which permanently abolished US slavery;

- slave shackles (1866) cut from the ankles of 17-year-old Mary Horn, who was held captive even after slavery was abolished the year before, until her fiancé asked for help from a Union soldier who removed the chains and married the couple;

- Uncle Ned’s School (1866) a sculpture by artist John Rogers depicting an improvised classroom created by African Americans during Reconstruction;

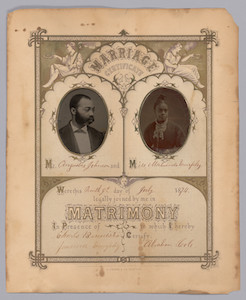

- marriage certificate (1874) of Augustus Johnson and Malinda Murphy, who made their long-standing relationship legal during Reconstruction;

- activist Ida B. Wells’ pamphlet Southern Horrors (1892), which reported that 728 lynchings had taken place in just the previous eight years and was written to “arouse the conscience of the American people to a demand for justice to every citizen”

To celebrate the opening of the exhibition, join three local scholars—Drs. William Green, Duchess Harris, and James Robinson—for a program on the history of African Americans in Minnesota during the post-Emancipation era. This opening program will take place from 1 pm–3 pm on Saturday, February 3 at the Minnesota History Center.

Funding provided by the State of Minnesota's Legacy Amendment, through the vote of Minnesotans on Nov. 4, 2008.

This exhibition has been organized by the New-York Historical Society. Lead support for the exhibition provided by National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor. Major support provided by the Ford Foundation and Crystal McCrary and Raymond J. McGuire.

Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in these programs do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

About the Minnesota Historical Society

The Minnesota Historical Society is a non-profit educational and cultural institution established in 1849. MNHS collects, preserves, and tells the story of Minnesota’s past through museum exhibits, libraries and collections, historic sites, educational programs, and book publishing. Using the power of history to transform lives, MNHS preserves our past, shares our state’s stories, and connects people with history.

About the New-York Historical Society

The New-York Historical Society, one of America’s preeminent cultural institutions, is dedicated to fostering research and presenting history and art exhibitions and public programs that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, New-York Historical has a mission to explore the richly layered history of New York City and State and the country, and to serve as a national forum for the discussion of issues surrounding the making and meaning of history. New-York Historical is also home to one of the oldest, most distinguished libraries in the nation—and one of only sixteen in the United States qualified to be a member of the Independent Research Libraries Association—the Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, which contains more than three million books, pamphlets, maps, atlases, newspapers, broadsides, music sheets, manuscripts, prints, photographs and architectural drawings.

MNHS media contacts: Allison Ortiz, 651-259-3051, allison.ortiz@mnhs.org , Jack Bernstein, 651-259-3058, jack.bernstein@mnhs.org or Nick Jungheim, 651-259-3060, nick.jungheim@mnhs.org

Unidentified artist

Dred Scott, after 1857

Oil on canvas

Reproduction. New-York Historical Society

Dred Scott was a Missouri slave who sued for his freedom. He argued that he had lived with his master in the state of Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, places where slavery was outlawed. Other slaves had been emancipated on these grounds. But in 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court decided against him. It said he had no right to sue because he was not a U.S. citizen. The justices ruled that no black person, free or enslaved, could ever be a U.S. citizen.

Download high-res image (23.71 MB)

United States Congress

Thirteenth amendment resolution, 1865

Reproduction. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC00263

In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution permanently abolished slavery in the U.S. Unlike the Emancipation Proclamation, which applied only to the Confederate states, it freed enslaved African Americans across the nation. As profound as it was, the Thirteenth Amendment left crucial questions unanswered. What was the legal status of America’s black population? What were their rights? They were free, but would they be citizens?

Download high-res image (41.98 MB)

John Rogers

Uncle Ned’s School, 1866

Bronze

New-York Historical Society, Gift of Mr. Samuel V. Hoffman

Popular sculptor John Rogers depicted one of the many improvised classrooms African Americans created during Reconstruction. Plaster casts of an original bronze sculpture were sold widely, bringing this sympathetic depiction of black life to a large audience. In this scene, “Uncle Ned” pauses in his work to assist one of his students with a question from her book. A mischievous young boy sits at his feet trying to distract them. In a popular song from the 1840s, “Uncle Ned” is a blind and docile slave. Here, a free “Uncle Ned” is teaching a child how to read—an act that had been a crime in some Southern states during slavery.

Download high-res image (23.96 MB)

Ballot box, ca. 1880-90

Wood, glass, and brass

New-York Historical Society, Gift of Roberta and Donald Gratz

African Americans embraced their newly acquired citizenship and took seriously their long-denied rights and responsibilities. Black men voted in large numbers and ran for office. Men and women joined patriotic clubs and local branches of the Republican Party. Black participation in local elections and state constitutional conventions created the first interracial governments in the United States. This demonstration of black citizenship aroused deep hostility among those who had only a few years earlier held African Americans as slaves.

Download high-res image (31.46 MB)

Winslow Homer (1836-1910)

A Visit from the Old Mistress, 1876

Reproduction

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of William T. Evans

A former slave holder, dressed in mourning, stands in the home of her former slaves. These black women have spent their lives bowing to whites, but now they show no sign of deference. Artist Winslow Homer, a wartime correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, captured the great shift in relations in the South

Download high-res image (186.16 KB)

Marriage certificate, 1874

Reproduction. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Louis Moran and Douglas Van Dine

Augustus Johnson and Malinda Murphy married on July 9, 1874, in Spencerport, New York. Many African Americans seized the simple freedom to make long-standing relationships legal. Under slavery, formal marriages of slaves had not been recognized.

Download high-res image (1.71 MB)

Kara Walker (b. 1969)

Maquette for the Katastwóf Karavan, 2017

New-York Historical Society, Purchase, Coaching Club Acquisition Fund

Contemporary African American artist Kara Walker uses silhouettes to depict slavery and racial stereotypes in her purposefully provocative work. “The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that’s also what the stereotype does.” Among the many figures are a chain gang and a woman collapsing in a cotton field. This piece is a miniature model for a large 2018 sculpture, installed for public view at Algiers Point, New Orleans.

Download high-res image (189.92 KB)

Maggie Walker and accountants using an adding machine, St. Luke’s Hall, 1917

Reproduction. Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, National Park Service

Maggie Walker, a gifted entrepreneur, created businesses to help Richmond, Virginia’s black community advance economically. When she started the St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank, she became the first black female bank president in the U.S. Other St. Luke’s enterprises included a newspaper, an insurance company, a clothing factory, and a store. All hired black workers, especially young women who otherwise had few job opportunities. Black consumers could now shop and conduct daily tasks safe from the abuses of Jim Crow

Download high-res image (32.94 MB)

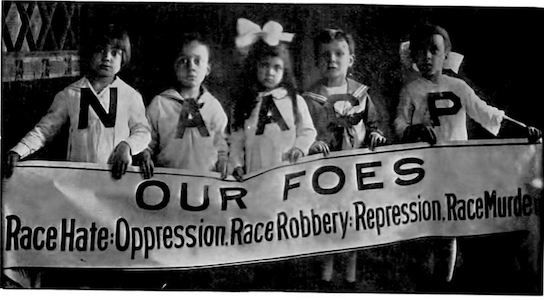

Photograph of young girls from The Crisis, May 1918

Reproduction. Indiana University Libraries

W.E.B. Du Bois and an interracial group of men and women founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) after an assault by whites on the black community in Springfield, Illinois, in 1908. The violence in Abraham Lincoln’s home town convinced many that Jim Crow was not simply a Southern problem. Du Bois launched and edited the organization’s magazine. He titled it The Crisis because he believed America was at a critical moment in its history. The magazine informed a national audience about important issues, built support for the NAACP’s mass protests and legal campaigns, and published the work of black writers and poets.

Download high-res image (82.49 MB)

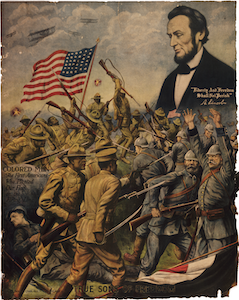

Charles Gustrine

True Sons of Freedom, 1918

Reproduction. The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC09121

Close to 400,000 black Americans served during World War I, but most had been drafted. Moreover, few African Americans saw combat because white military officers believed blacks were better suited to manual labor duties. The example set by the Harlem Hellfighters—which spent more time in continuous combat than any other American unit—directly challenged those prejudices.

Download high-res image (50.91 MG)